World War II

Invasion of Sydney Harbour, 31 May 1942 by Japanese midget submarines

In October 1907, my grandfather, John Fuller Junr., on his World Tour, observed the Japanese nation during his ten day working holiday in Tokyo, when he described Japan as a hermit nation. A hermit nation is a country which isolates itself from the world with its customs, language and culture – rather like modern North Korea today. There would not have been many men from New Zealand who had ever visited Japan in 1907 and so Johnny’s description of his visit to Tokyo is a unique and most interesting account of his prediction about the build-up of arms by the Japanese for their future expansion. He stated that there were 50 million people living in Japan, but only 3 million of them paid tax, an interesting observation when he also pointed out that unless one paid tax, they didn’t have a vote. To become eligible to vote, a person needed to pay 15 Yen per annum for the privilege.

Marlborough Express, 15 January 1908

John Fuller Junr. recognised the inherent power of Japan, after observing their amazing and decisive defeat of the Russians in 1905 at the Battle of Mukden. John saw first-hand the Japanese naval ships lying in Yokohama Harbour in 1907 when, aboard the Hong Kong Maru, he arrived in Japan along with his wife Gertie. In his journal he stated “It seems quite remarkable that this hermit nation could go to war and beat Russia and could read the riot act to Australasia as easily as falling off a log.” 5 October 1907, Tokyo, Japan. I realised that Johnny, in his inimitable way was actually predicting World War 2, three decades later. He was issuing a warning for New Zealanders to wake up to this real threat of war. He also realised the importance of an alliance with the United States of America and applauded their haste to protect the Philippine Islands.

Australia and New Zealand had increasingly become alarmed about security in their remote part of the Southern Hemisphere in the early 1900’s. After the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance (renewed in 1905) allowed the Royal Navy (RN) to reduce its Pacific presence. The RN had a presence in Sydney Harbour with the Australian government contributing £200,000 per annum for its upkeep. Australia still had no substantial Navy of its own, just a few years after Australia’s Federation. Worse still, the RN Squadron could be withdrawn in times of danger to fulfil other imperial priorities, leaving Australia and NZ vulnerable.

John Fuller Junr. predicted the build-up of Japan’s military and naval might, which later resulted in a potential and very real threat of invasion of Australia’s east coast from Queensland down to New South Wales. Japan was dynamically poised to use war in WW2 in Europe as a cover for them to expand their territories into the Pacific region, which had been left unprotected by the war in Britain and Europe against Germany. The bombing of Pearl Harbour 7 December 1941, the shock invasion of Singapore from the north in 8 February 1942 and the chaotic retreat of the British Army personnel dashing to Singapore’s Harbour to board leaving ships, was a telling sign of deterioration in the Pacific. The fall of Singapore caused the incarceration of entire British and Australian Regiments, arrested as Prisoners of War into the arms of a brutal Japanese regime which left Australia and other Pacific nations in a perilous position.

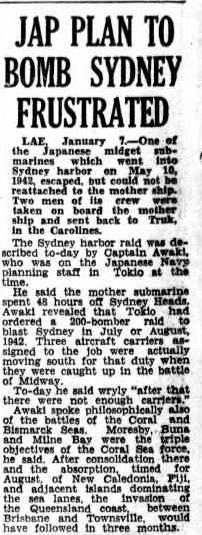

Thankfully, the American fleet that survived Pearl Harbour’s bombing in Hawaii had enough naval power to mount an offensive in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Unbeknown to the Australian general public, there was a massive plan by the Japanese to invade and take control of Sydney in either July or August of 1942. This on top of the bombing raid of Sydney Harbour on 31 May 1942 by midget submarines and the bombing of Sydney’s eastern suburbs from the Submarine “mother ship” on 8 June 1942, when 12 bombs shelled Bellevue Hill, Rose Bay and Bondi. It also appears from reports that 200 Japanese bombing aircraft were poised to attack Sydney a few months later, however, at the last moment, the Battle of the Midway on 4 – 7 June 1942, north west of Hawaii, diverted Japanese man power to another theatre of war. Many Japanese aircraft carriers were destroyed leaving them unable to advance their intentions to invade Australia. This incredibly is the true story about how close Sydney and potentially Australia came to being overtaken by the Japanese military forces.

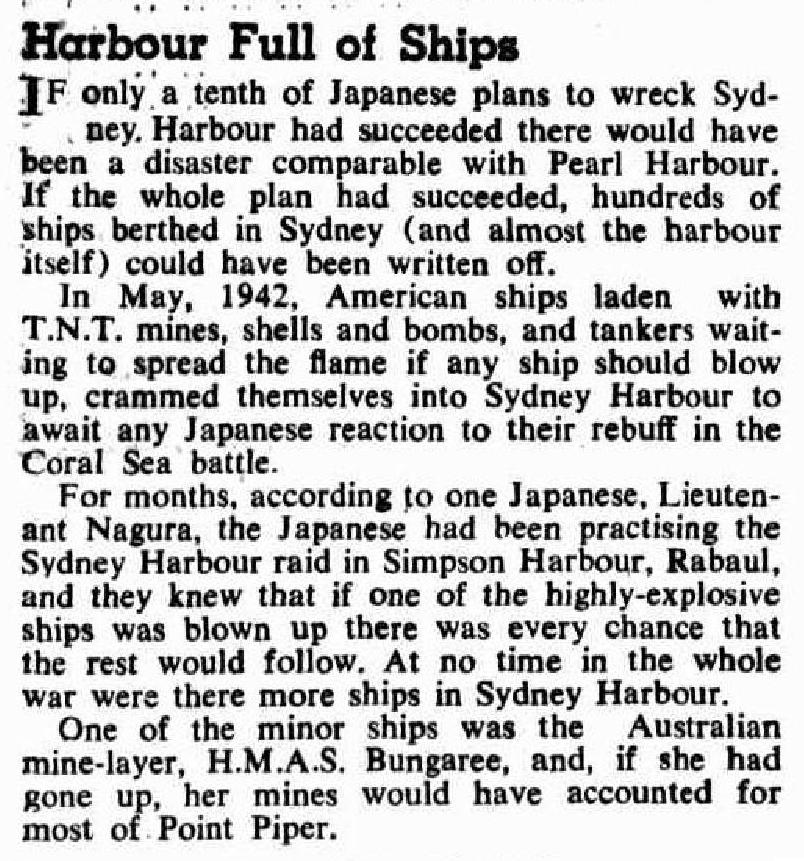

The Japanese had been practicing the invasion of Sydney Harbour at Simpson Harbour, Rabaul, New Guinea. Plans of the enormity of this invasion were only revealed after WW2 in 1949, when an investigation into the bombings finally took place. In late May 1942, many American ships laden with TNT, mines, shells and bombs were sheltering in Sydney Harbour, cramming themselves into the harbour awaiting the Japanese reaction to their rebuff in the Battle of the Coral Sea, a fierce battle between 4-8 May 1942.

It turns out that on the night of 31 May 1942 Sydney Harbour came very close to being annihilated by four midget submarines who were intent on blowing up U.S. warships moored in the harbour. This in turn would have blown up much of the surrounding harbour foreshores – the city centre bordering Circular Quay probably would have been included in this obliteration. It is stated in the Western Mail, Perth 9 June 1949 “One of the minor ships was the Australian mine-layer, H.M.A.S Bungaree, and, if she had gone up, her mines would have accounted for most of Point Piper.”

Western Mail, Perth, 9 Jun 1949

Interestingly Point Piper was shunned for many decades after World War 2 by Sydneysiders, who preferred to opt for safety, rather than live in this exposed harbour suburb. Many homes there were unsellable and became boarding houses as a result. When my parents purchased ‘Routala’ at 64 Wunulla Road, Point Piper in 1954, it was exactly that, an old boarding house, with a series of large bedrooms with a sink installed in a corner of each bedroom. It was a huge undertaking for my parents, Reg and Vena Robson, to turn this old boarding house back into a family home again. Indeed throughout my childhood, a sink stood in the corner of my bedroom until the early 1970’s.

My family lived at ‘Routala’ 64 Wunulla Road, Point Piper, until 1998, a period of 45 years, which saw the suburb turn from a pariah area into a sought after suburb close to the city.

A real estate agent directing my parents to a suitable home in 1954, took them to Vaucluse, where they viewed several houses, however my parents deemed the area to be too remote from the city. Just at that point, the agent identified a house across Rose Bay at Point Piper, explaining that there was a large waterfront boarding house at the end of the point up for sale, that had been stubbornly lacking buyers’ interest. My parents bought this home for £16,000, a lot of money in those day, but in today’s calculation in 2022, that was just over $307,000.

My mother was widowed in 1980 and whilst she had been left fairly well off, the Carr Labor Government in 1997, in a shocking cash grab, decided to impose an annual land tax levy on the unimproved land value of perceived wealthy home owners; accordingly my mother received a land tax bill for $110,000 later that year. Forced to pay this amount per annum, or allow the debt to accumulate, with a resultant “J” curve shaped interest rate until her death, meant she had no alternative but to sell.

During World War 2, Sydney was theoretically a well-protected port, although her harbour boom defences had not yet been completed at the heads by May 1942, this then allowed the midget submarines to infiltrate the harbour heads, some suggesting that the midget submarines hid under a Manly Ferry whilst it negotiated the boom at the heads. Some sources claimed that the midget submarine navigators were in fact kamikaze warriors who knew they were to be sacrificed as soon as they left their mother submarines, which was skulking some miles south off the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. The midget submarines were very cramped and uncomfortable inside, however, a crew of two could live in them for a considerable period of time. They were powerful with a surface speed of 25 knots.

The attack on Sydney Harbour began at 8.15pm when a watchman on the boom defence at Sydney heads saw a periscope just inside the boom. He shouted out to the H.M.A.S. Yarromoa which was keeping a lookout near the West Gate. The boat tore towards their quarry, and blew the submarine’s hull up by depth charges. The news quickly spread, 13 Allied warships, including H.M.A.S Canberra and U.S.S. Chicago, as well as Silver Cloud, Steady Hour, Sea Mist, Winbah, Marlean and Toomeree put out immediately from Farm Cove to protect the foreshore. Another midget submarine which had gained entry to Sydney Harbour let a torpedo out in the direction of the Chicago, passing just under the keel and running up under the Gun Wharf at Garden Island, where it failed to explode. The second torpedo sank the old ferry steamer, the Kuttabul, which was being used as a temporary naval depot ship, tragically killing 31 men. Thankfully this was the only success the Japanese had in their Sydney Harbour strike. The Chicago and H.M.A.S. Whyalla saw the submarine near to the Sydney Harbour Bridge and fired at her with everything they had, depth chargers from the Yandra in all probability destroyed the submarine. Ferry passengers on Sydney Harbour terrifyingly found themselves in the middle of a series of fierce shellings and several ferries were forced to go about to seek shelter.

Western Mail, Perth, 9 Jun 1949 (Cont.)

Daily Mercury, 8 January 1946

The very fact that Australians were not told about any impending invasion was probably a secret Federal Government decision to protect and conceal the seriousness of the threat to Australia, especially in light of the bombings in Darwin Harbour in February 1942, that were to a certain degree hushed up by the Australian War Office until the end of the war. The shocking reality was that the Australian War Office was in no way able to fight off an invasion as most of their more able soldiers were already in Europe and Africa fighting a war on the other side of the war.

Left behind in Australia were a group of army Generals and their personnel who were not called up for active service, due mainly to the fact that they were older men. Some had an empirical idea about the impenetrable myth that war would never come to Australia. How wrong they were.

Cloncurry Advocate, 20 February 1942

My mother Vena Fuller and her aunt Ethel Moar stood at the top of Bellevue Hill at Ginahgulla Road, outside her home ‘Caerleon’ the night of 31 May 1942 and later told our family the story that Sydney Harbour had lit up like daylight with the bombing frenzy taking place on the harbour. It must have been a terrifying sight to see all the previously docked ships moving away from their ports and anchors to protect the land and prevent themselves from sitting as stationary targets. At the time my mother was a VAD working at Red Cross Headquarters, her job as a driver was to pick up and drop off Australian and American officers to the various war bases around Sydney.

Close to Taylor’s Bay in Sydney Harbour at 5.30am on 1 June 1942, a section of a submarine was found. Sea Mist dropped two depth charges and a terrific explosion bought the submarine rapidly to the surface. It was reported that four subs had attempted to enter Sydney Harbour, the Japanese later claimed only three, however one submarine may not have gained entry to the harbour and is reported to have been found many decades later on the bottom of the sea bed off Broken Bay, north of Sydney in November 2005.

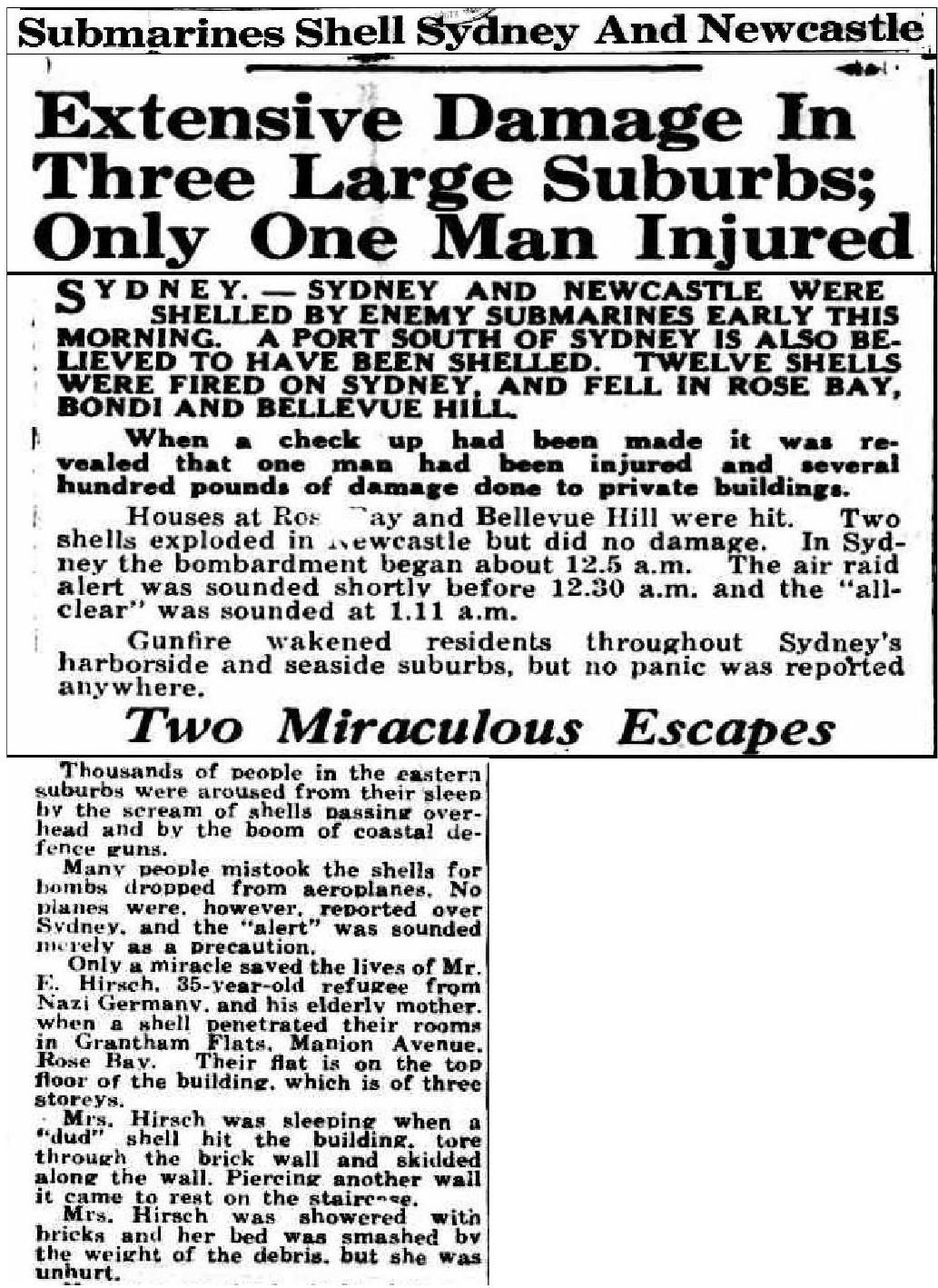

My mother, also used to tell the story about the night Sydney’s eastern suburbs came under shell fire launched from submarines off the Sydney coast. She was awoken in the early hours of 8 June 1942 to the sound of bombs going off very near to her Bellevue Hill home. It was a terrifying experience, however everyone kept calm and refused to panic in the face of the attack. My mother being a stoic by nature, was always going to be brave in the face of an enemy. Some days following the bombings, she inspected the damage to a flat building in Plumer Road, Rose Bay and also claimed that there were reports of bombs landing on nearby Woollahra and Royal Sydney Golf Courses. As children in the 1960’s, my sister and I were shown the exact place in Plumer Road where the bomb had detonated. Today, the old block of flats still exists on the corner of Plumer Road and Salisbury Roads.

Barrier Miner, Broken Bay, 8 June 1942

Sydney Morning Herald, 22 February 1943

Interestingly, very few newspapers from Sydney reported these terrifying bombing incidents upon Sydney Harbour and in the main, they played down its dangerous significance, due to a lucky break with the discovery of the Japanese submarines’ incursion into Sydney Harbour at the booms. It is also interesting to see that the Chicago was not unknown to Sydneysiders, having visited in March 1941, well before Pearl Harbour’s bombing on 7 December 1941.

Queensland Times 19 March, 1941

At no time did Sydney newspapers ever indicate that another bombing invasion by Japanese forces was imminent. I have enjoyed bringing this short piece of my family history to light, to show yet again, how my family always stayed strong in times of adversity.

Lavinia “Vena” Fuller, VAD driver for Red Cross Headquarters, Sydney, 1940-1945

Virginia Rundle

15 March 2022

Acknowledgment

Thanks must go to Trove Digitised Newspapers for their fabulous online early Australian Newspaper collection as well as Papers Past, in New Zealand, which has allowed me many hours of research into my family history.